Showing posts with label Women of the Desert. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Women of the Desert. Show all posts

Thursday, November 14, 2019

Wednesday, March 6, 2019

Letter from the Zapatista Women to Women in Struggle Around the World !

ZAPATISTA ARMY FOR NATIONAL LIBERATION

MEXICO

February 2019

To: Women in struggle everywhere in the world

From: The Zapatista Women

Sister, compañera:

We as Zapatista women send you our greetings as the women in struggle that we all are.

We have sad news for you today, which is that we are not going to be able to hold the Second International Encounter of Women in Struggle here in Zapatista territory in March of 2019.

Maybe you already know the reasons why, but if not, we’re going to tell you a little about them here.

The new bad governments have said clearly that they are going to carry forward the megaprojects of the big capitalists, including their Mayan Train, their plan for the Tehuantepec Isthmus, and their massive commercial tree farms. They have also said that they’ll allow the mining companies to come in, as well as agribusiness. On top of that, their agrarian plan is wholly oriented toward destroying us as originary peoples by converting our lands into commodities and thus picking up what Carlos Salinas de Gortari started but couldn’t finish because we stopped him with our uprising.

All of these are projects of destruction, no matter how they try to disguise them with lies, no matter how many times they multiply their 30 million votes. The truth is that they are coming for everything now, coming full force against the originary peoples, their communities, lands, mountains, rivers, animals, plants, even their rocks. And they are not just going to try to destroy us Zapatista women, but all indigenous women—and all men for that matter, but here we’re talking as and about women.

In their plans our lands will no longer be for us but for the tourists and their big hotels and fancy restaurants and all of the businesses that make it possible for the tourists to have these luxuries. They want to turn our lands into plantations for the production of lumber, fruit, and water, and into mines to extract gold, silver, uranium, and all of the minerals the capitalists are after. They want to turn us into their peons, into servants who sell our dignity for a few coins every month.

Those capitalists and the new bad governments who obey them think that what we want is money. They don’t understand that what we want is freedom, that even the little that we have achieved has been through our struggle, without any attention, without photos and interviews, without books or referendum or polls, and without votes, museums, or lies. They don’t understand that what they call “progress” is a lie, that they can’t even provide safety for all of the women who continue to be beaten, raped, and murdered in their worlds, be they progressive or reactionary worlds.

How many women have been murdered in those progressive or reactionary worlds while you have been reading these words, compañera, sister? Maybe you already know this but we’ll tell you clearly here that in Zapatista territory, not a single woman has been murdered for many years. Imagine, and they call us backward, ignorant, and insignificant.

Maybe we don’t know which feminism is the best one, maybe we don’t say “cuerpa” [a feminization of “cuerpo,” or body] or however it is you change words around, maybe we don’t know what “gender equity” is or any of those other things with too many letters to count. In any case that concept of “gender equity” isn’t even well-formulated because it only refers to women and men, and even we, supposedly ignorant and backward, know that there are those who are neither men nor women and who we call “others” [otroas] but who call themselves whatever they feel like. It hasn’t been easy for them to earn the right to be what they are without having to hide because they are mocked, persecuted, abused, and murdered. Why should they be obligated to be men or women, to choose one side or the other? If they don’t want to choose then they shouldn’t be disrespected in that choice. How are we going to complain that we aren’t respected as women if we don’t respect these people? Maybe we think this way because we are just talking about what we have seen in other worlds and we don’t know a lot about these things. What we do know is that we fought for our freedom and now we have to fight to defend it so that the painful history that our grandmothers suffered is not relived by our daughters and granddaughters.

We have to struggle so that we don’t repeat history and return to a world where we only cook food and bear children, only to see them grow up into humiliation, disrespect, and death.

We didn’t rise up in arms to return to the same thing.

We haven’t been resisting for 25 years in order to end up serving tourists, bosses, and overseers.

We will not stop training ourselves to work in the fields of education, health, culture, and media; we will not stop being autonomous authorities in order to become hotel and restaurant employees, serving strangers for a few pesos. It doesn’t even matter if it’s a few pesos or a lot of pesos, what matters is that our dignity has no price.

Because that’s what they want, compañera, sister, that we become slaves in our own lands, accepting a few handouts in exchange for letting them destroy the community.

Compañera, sister:

When you came to these mountains for the 2018 gathering, we saw that you looked at us with respect, maybe even admiration. Not everyone showed that respect—we know that some only came to criticize us and look down on us. But that doesn’t matter—the world is big and full of different kinds of thinking and there are those who understand that not all of us can do the same thing and those who don’t. We can respect that difference, compañera, sister, because that’s not what the gathering was for, to see who would give us good reviews or bad reviews. It was to meet and understand each other as women who struggle.

Likewise, we do not want you to look at us now with pity or shame, as if we were servants taking orders delivered more or less politely or harshly, or as if we were vendors with whom to haggle over the price of artisanship or fruit and vegetables or whatever. Haggling is what capitalist women do, though of course when they go to the mall they don’t haggle over the price; they pay whatever the capitalist asks in full and what’s more, they do so happily.

No compañera, sister. We’re going to fight with all our strength and everything we’ve got against these mega-projects. If these lands are conquered, it will be upon the blood of Zapatista women. That is what we have decided and that is what we intend to do.

It seems that these new bad governments think that since we’re women, we’re going to promptly lower our gaze and obey the boss and his new overseers. They think what we’re looking for is a good boss and a good wage. That’s not what we’re looking for. What we want is freedom, a freedom nobody can give us because we have to win it ourselves through struggle, with our own blood.

Do you think that when the new bad government’s forces—its paramilitaries, its national guard—come for us we are going to receive them with respect, gratitude, and happiness? Hell no. We will meet them with our struggle and then we’ll see if they learn that Zapatista women don’t give in, give up, or sell out.

Last year during the women’s gathering we made a great effort to assure that you, compañera and sister, were happy and safe and joyful. We have, nevertheless, a sizable pile of complaints that you left with us: that the boards [that you slept on] were hard, that you didn’t like the food, that meals were expensive, that this or that should or shouldn’t have been this way or that way. But later we’ll tell you more about our work in preparing the gathering and about the criticisms we received.

What we want to tell you now is that even with all the complaints and criticisms, you were safe here: there were no bad men or even good men looking at you or judging you. It was all women here, you can attest to that.

Well now it’s not safe anymore, because capitalism is coming for us, for everything, and at any price. This assault is now possible because those in power feel that many people support them and will applaud them no matter what barbarities they carry out. What they’re going to do is attack us and then check the polls to see if their ratings are still up, again and again until we have been annihilated.

Even as we write this letter, the paramilitary attacks have begun. They are the same groups as always—first they were associated with the PRI, then the PAN, then the PRD, then the PVEM, and now with MORENA.

So we are writing to tell you, compañera, sister, that we are not going to hold a women’s gathering here, but you should do so in your lands, according to your times and ways. And although we won’t attend, we will be thinking about you.

Compañera, sister:

Don’t stop struggling. Even if the bad capitalists and their new bad governments get their way and annihilate us, you must keep struggling in your world. That’s what we agreed in the gathering: that we would all struggle so that no woman in any corner of the world would be scared to be a woman.

Compañera, sister: your corner of the world is your corner in which to struggle, just like our struggle is here in Zapatista territory.

The new bad governments think that they will defeat us easily, that there are very few of us and that nobody from any other world supports us. But that’s not the case, compañera, sister, because even if there is only one of us left, she’s going to fight to defend our freedom.

We aren’t scared, compañera, sister.

If we weren’t scared 25 years ago when nobody even knew we existed, we certainly aren’t going to be scared now that you have seen us—however you saw us, good or bad, but you saw us.

Compañera, hermana:

Take care of that little light that we gave you. Don’t let it go out.

Even if our light here is extinguished by our blood, even if other lights go out in other places, take care of yours because even when times are difficult, we have to keep being what we are, and what we are is women who struggle.

That’s all we wanted to say, compañera, sister. In summary, we’re not going to hold a women’s gathering here; we’re not going to participate. If you hold a gathering in your world and anyone asks you where the Zapatistas are, and why didn’t they come, tell them the truth: tell them that the Zapatista women are fighting in their corner of the world for their freedom.

That’s all, compañeras, sisters, take care of yourselves. Maybe we won’t see each other again.

Maybe they’ll tell you not to bother thinking about the Zapatistas anymore because they no longer exist. Maybe they’ll tell you that there aren’t any more Zapatistas.

But just when you think that they’re right, that we’ve been defeated, you’ll see that we still see you and that one of us, without you even realizing it, has come close to you and whispered in your ear, only for you to hear: “Where is that little light that we gave you?”

From the mountains of the Mexican Southeast,

The Zapatista Women

February 2019

Labels:

Women of the Desert

Wednesday, February 28, 2018

Duka Girls Of Mongolia...

Labels:

Women of the Desert

Tuesday, August 8, 2017

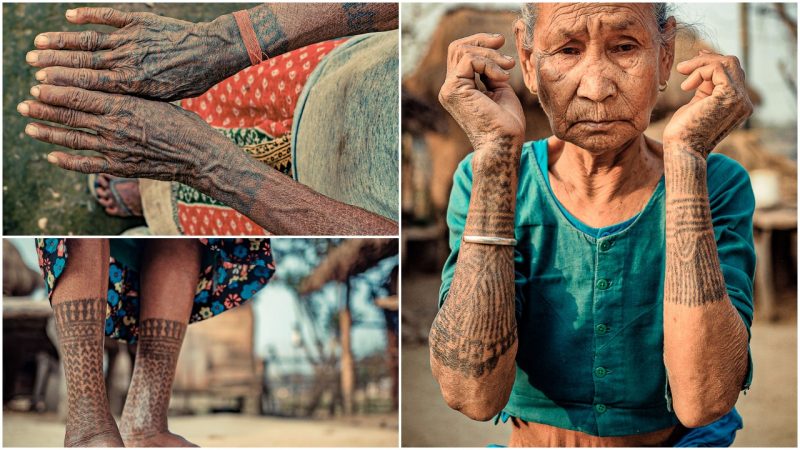

The Last Of The Tattooed Women Of The Tharu Tribe...

Wonderful and unusual people can be found all over the globe. Many diverse civilizations have already vanished as a result of globalization and many are on the verge of extinction, their culture becoming forever lost.

Acknowledging the sadness of this loss, and recognizing the importance of such cultures–becoming ever rarer–photographers are traveling the globe and documented those they meet. It is thanks to those encounters that we can come to learn more and broaden our perspectives beyond the familiar. One such photographer is Omar Reda, the man who, through his passion, has given the world a number of fascinating images.

Omar Reda is a Lebanese creative director at the Genesis Riyadh consulting agency, where he has worked since 2013, based in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. He began his career in 2005 working for Y&R/Riyadh, after graduating in graphic design from the Notre Dame University. He has had a fortunate career path, having worked for some of the biggest companies in the world. Omar’s other passion, alongside graphic design, is photography. With his camera in hand, he travels extensively. One of the places he has visited was Nepal, where he documented the tattooed women of the Tharu tribe, practicing a tradition that may be ending.

The Tharu peoples are an indigenous ethnic group that live in the southern foothills of the Himalayas. In 2011, the estimated population of the Tharu was approximately 1.7 million, with the majority living in Nepal. Most of these forest people, as they refer to themselves, are Hindu by religion, and survive on agriculture and hunting. They are a people who’ve thrived in isolation. and many varieties of their endemic language still exist.

A lot can be found in the Chitwan District of Nepal, where Omar Reda met them and took his intriguing photos. On his visit to Nepal, Omar discovered that the women of the Tharu tribe would have, in the past, all be covered in tattoos. It is not rare for indigenous nations to practice the art of tattooing, but the reasons behind the tattoos of the Tharu women shocked the adventurous photographer.

There were three different stories that Omar learned about the tattoos. The first, and most shocking one, tells of how the beautiful girls of the Tharu people were taken as sex slaves by the royal family that ruled the Kingdom of Nepal. Chitwan was the area where the members of the royal family once spent their summers. The constant abduction of the Tharu beauties made the women put tattoos on their bodies, so that they would look ugly to the royal men.

The second story explains that the tattooing was mandatory for teenage girls. If the girl did not have these tattoos, then she would be expelled from the community, as well as from her family. Non-tattooed women were not allowed to marry or even talk to other people.

The Tharu went so far as to forbid people from taking anything that a woman without a tattoo had previously touched. So, in order to be accepted by their people, the Tharu girls had to cover their bodies with ink.

The third story is the least shocking one. It says that the tattoos were done in order to enhance the beauty of the women so that when they die, they will go to heaven in the most beautiful form. It is not certain which of the three stories is true. It may be none, or it might be all; however, it is certain that the art of tattooing played a very important role among these people.

Nepal is not the only place where Omar Reda has taken photos. Many of his incredible images can be found on his personal website or Instagram account; photos from Turkey, Tanzania, India, and many other beautiful countries where Omar has captured some of the rich and unique cultures still remaining around the world.

Labels:

Women of the Desert

Tuesday, June 20, 2017

Friday, March 24, 2017

The Women Of Panjshambe Bazaar...

A strikingly dressed Bandari woman at her stall in Iran’s Panjshambe Bazaar. African and Indian influences are evident throughout the Gulf Coast region. Photo: Brook Mitchell

Each week, Panjshambe Bazaar attracts visitors from all over the region who come to experience the vibrant mix of African, Asian and Arab influences that make up the local tribes, known as the Bandari, which means ‘people of the port’ in Persian.

An Australian photographer captured these amazing images of Minab in Iran. Photo: Brook MitchellSource:Diimex

Here, in stark contrast to the plain black burqas and niqabs seen elsewhere in the Middle East, the women are draped in colour and wear a decorative face mask — made of metal and covered in cloth. The mask dates back to the days of Portuguese colonial rule and was originally worn to deflect the attentions of slave masters, who were always on the hunt for the prettiest girls.

A Bandari woman in the Panjshambe Bazaar (Thursday Market). Photo: Brook MitchellSource:Diimex

Australian-born, Bali-based photographer Brook Mitchell was given the opportunity to document this remarkable place, in all its colourful glory.

“Each mask’s design is determined by the different tribal groups, and the wearing of it is considered a sign of a girl coming of age,” Mitchell told news.com.au. “It apparently helps in a dust storm as well — which are frequent in the area.

A Bandari women in the livestock section of the weekly 'Panjshambe Bazaar'. Photo: Brook MitchellSource:Diimex

“It’s not considered by the locals as oppressive. It’s a legal requirement in Iran for women to wear the head scarf and full length clothing, though these masks are unique to the southern region and small pockets in other Gulf countries. As far as I understand it they have strong cultural significance.”

Sellers at the 'Panjshambe Bazaar'. Photo: Brook MitchellSource:Diimex

Mitchell said Minab was becoming increasingly difficult for international travellers to access because of the current religious and political unrest in the region.

“Good people suffering under an oppressive government is what I think of my time there,” he said.

Goats aplenty at the 'Panjshambe Bazaar'. Photo: Brook MitchellSource:Diimex

“People I met across the country were overwhelmingly open, friendly and curious towards me, especially in the south where tourists are not common. I hope things improve for them soon.

“It’s not so often as a photographer you get to visit a place so visually rewarding that’s also been little visited by outsiders, at least in recent times. I was pretty lucky to get in and see what I did.”

A local Bandari man. Photo: Brook MitchellSource:Diimex

A Bandari woman wearing a distinctive red mask. Photo: Brook MitchellSource:Diimex

A mural depicting local customs on the island of Hormuz, Persian Gulf. Photo: Brook MitchellSource:Diimex

A Bandari woman in the weekly 'Panjshambe Bazaar'. After sharing a simple breakfast of fruit and tea with the photographer this woman was happy for her picture to be taken, something of a rare occurrence in conservative Islamic areas. The bright masks worn by the Bandari are unique to this part of Iran and are said to be a cultural adornment rather than a religious one. Photo: Brook MitchellSource:Diimex

Even the local artwork captures the Bandari’s striking masks. Photo: Brook MitchellSource:Diimex

A carpet seller at the weekly 'Panjshambe Bazaar', Minab, Iran. Photo: Brook MitchellSource:Diimex

*www.news.com.au/travel/travel-ideas/adventure/iran-like-youve-never-seen-it/news-story/9e6dcbbe6b201c96e2dc6b033b468776

Labels:

Women of the Desert

Sunday, March 5, 2017

6 Matriarchies Still Functioning Today...

Mosuo

The Mosuo of China (living in the foothills of the Himalayan Mountains) are one of the best-known examples of a matrilineal society, where inheritance is passed down the female line and women have their choice of partners. In fact, they practice something called a "walking marriage," which is essentially the practice of women choosing their partner by walking to his home—and many women have multiple partners/marriages. Children take their mother's name and live with their mothers, while the men may or may not be involved in the raising of the kids. They often live with extended families in large households, with women handling all business decisions. Men often play a role politics, but the most respected person in any household is the grandmother. (For more insight, check out this short documentary.)

Fun fact: There is no word in their language for "father" or "husband."

Minangkabau

Also known as Minang, this group is located in Indonesia, and is matrilineal in that property, land, and inheritance is passed from mother to daughter. Low inheritance—such as income—is passed from father to son. In the past, this kept women in power, but now, "low income" is taking precedent and making a bit of a change in their modernizing society. Lineage is still traced through the mother's line, though, and the mother is the head of the family. Grooms are traditionally "given away" to the bride by female members of his family, who escort him to the home of the bride. Power and authority are generally shared between men and women, with women ruling the "domestic" sphere and men ruling the political and spiritual roles. Both genders believe this gives each equal footing. While the clan chief is male, women select the chief and have the power to remove him should he fail as a leader.

Akan

The Akan society is a multi-ethnic group in Ghana, where everything centers around a matriclan, clans founded by women. Men are often leaders of the clan, but their power comes from matrilineal lines—meaning power is descended through the man's mothers and sisters. Men not only support their own families, but also the families of his female relatives. Women conduct many rites and ceremonies—like funerals—and are typically leaders in the food and domestic spheres.

Bribri

Located in Costa Rica and northern Panama, the Bribri is a matrilineal line where women inherit the lands and create extended families. Children enter the mother's clan, and grandmothers are seen as the arbiters of tradition and knowledge. While men take on roles of importance, they are not allowed to "pass on" this knowledge or job to their sons, but rather only to their female relatives' sons. Women are given the right and ritual to prepare the cacao used in sacred Bribri rituals, giving them utmost importance in any clan.

Garo

An indigenous group in India and Bangladesh, Garos take clan titles from their mothers, with the youngest daughters inheriting property from their mother. While the society is matrilineal, men do hold power and are given the right to govern.

Tuareg

Tuareg are Berber people who live a nomadic lifestyle living in the Saharan dessert. In society, women have high status and the tribes are organized into confederations, where many women hold the power of reading and writing, with men herding livestock. Livestock and other movable property, however, are owned largely by women, whereas personal property is owned and inherited regardless of gender. The Tuareg are Muslim but are also influenced by their pre-existing beliefs—including matrilineal customs.

*www.marieclaire.com/culture/a19105/matriarchies-still-exist-today

Labels:

Women of the Desert

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)